“Heartily do we congratulate you and your country on this humane and righteous course. We assume that you cannot now stop short of the complete uprooting of slavery.”

– Working-men of Manchester, England

Address of the Working-Men of Manchester to President Lincoln; December 31, 1862

While division over the expansion of slavery across the United States, and with it the growth of the institution’s political influence, played a central role in the escalations contributing to the Civil War, the issue was largely absent from the conflict’s first years. In the hope of avoiding further secession or decline in support from the Northern public, the Lincoln administration avoided publicly aligning their efforts with any emancipationist cause. For their part, the South sought to avoid drawing connections between their own struggle and the preservation of slavery through an independent Confederacy.

These interests shaped early diplomatic framing of the conflict to foreign onlookers, but interests remained in how the issue was connected to the war. This was particularly true among the nations of Europe, where anti-slavery movements had encountered success earlier in the 19th century. Britain had made significant strides towards the abolishment of slavery and the end of the African slave trade in the Atlantic. Slavery was gradually phased out, first through the outlawing of the slave trade throughout the Empire, then through direct acts of emancipation, beginning in 1833.

International action against the smuggling of slaves grew through the 1830s and 40s, but regarding Anglo-American cooperation, progress was limited. An agreement prior to the Civil War – the 1842 Webster-Ashburton Treaty ending territorial disputes between British Canada and Maine, set forth the issue of the slave trade. Identifying it’s end as an additional interest of both parties, the door was opened to coordination, though extensive cooperation remained off the table.

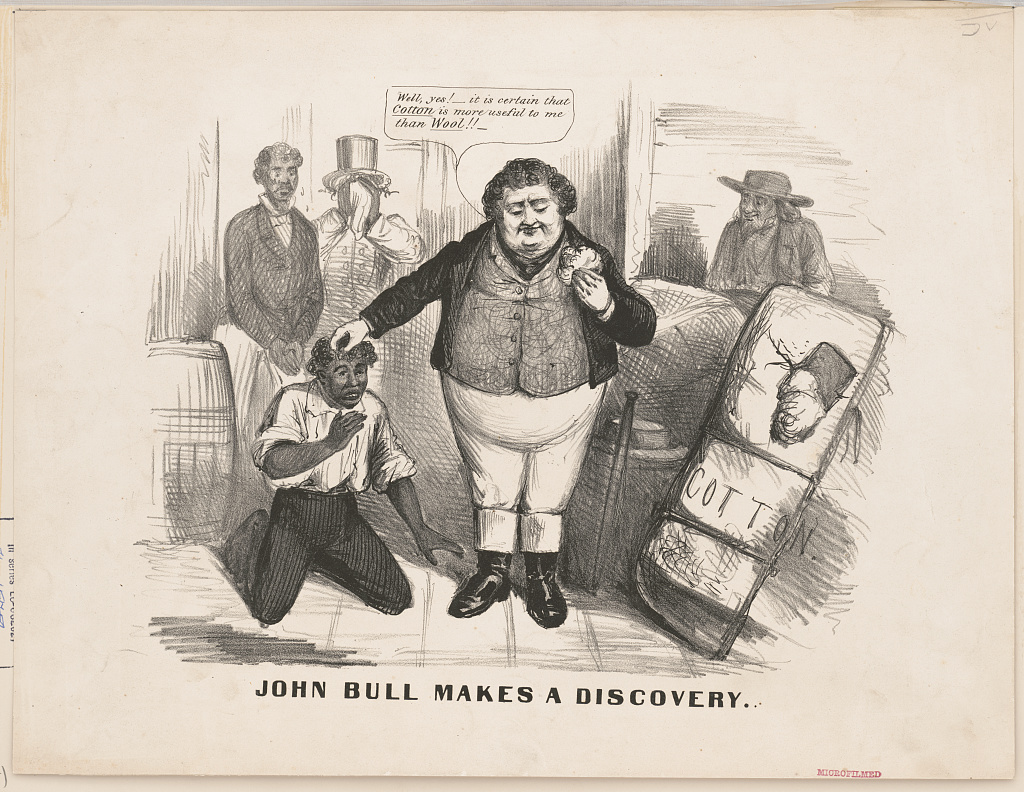

(Image from the Library of Congress)

By the time of the Civil War, the ardent anti-slavery stance of Britain had waned in its fervor, though such feeling remained widespread. Abolitionist sentiments still persisted among the varied societies dedicated to the institution’s end, but other concerns competed with anti-slavery interests. Economic issues stemming from the conflict in America, chief among them fluctuation in the cotton supply to the U.K’s industrial centers, pressured British society and Parliament. The American South’s reliance upon slavery for agriculture, and Britain’s economic connections to the region, led to questions of the Empire’s neutrality.

A further problem emerged in the framing of the war, particularly by the North. Argued as a war to reunify the country, rather than one focused on the issue of slavery, the justifications given garnered criticism, more susceptible to undermining by Southern counteraccusations of tyranny. Though not acknowledged by either side, connections to the issue of slavery remained perceptible to foreign onlookers, shaping their perception of the conflict. Even among traditional abolitionist groups in the Empire, such as the pacifist Quakers, a war fought to end slavery did not justify unrest and bloodshed.

Following the controversial Trent Affair of 1861, an escalation of tension between the U.S. and U.K nearing to war, American efforts to facilitate amity between the two centered upon slavery. As Lincoln planned to take action on the issue, to be announced in late 1862, talks between the British envoy, Lord Lyons, and Secretary of State Seward produced a new agreement. The Lyons-Seward treaty resulted in new efforts against the slave trade, affording military vessels of both nations the right of search of the other’s trade ships.

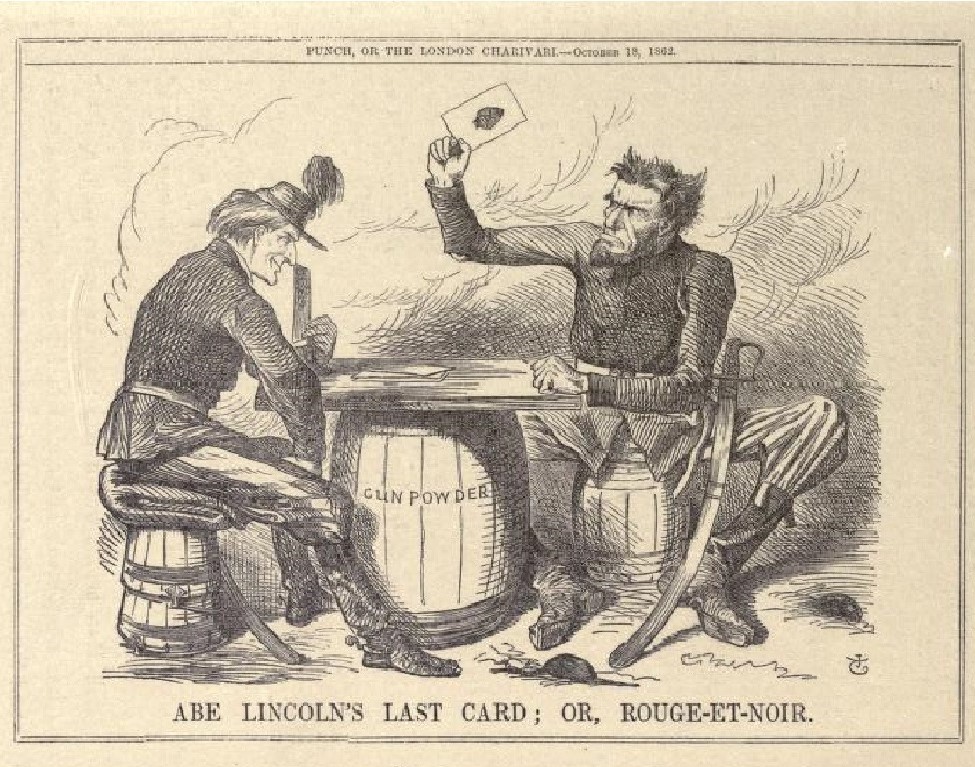

Punch, October 18, 1862

Image from Abraham Lincoln and the London Punch, by William Walsh, 1909.

“The emancipation scheme of the North is condemned in advance by the insincerity of its motive, since its authors scarcely care to deny that they regard it purely as a military measure to “crush the rebellion;””

– Henry Hotze, Confederate Propagandist in London

“A Word for the Negro,” The Index, February 12, 1863

The announcement of Lincoln’s plans for emancipation had mixed initial reaction. It’s purpose, to clearly define the war – particularly for those outside the country – as one between liberty and democracy, and slavery, would be met, but not without overcoming doubt and derision. Confederates in America and abroad downplayed the initial framework of the measure, noting the limits of its power, with loose support in the North to see it through the end of the war.

Such argument, expressed by agents such as Henry Hotze in the quote above, influenced early doubts in Britain. The U.S. had debated the matter of slavery for decades prior to the outbreak of war. The Union’s initial framing of the conflict, and initial efforts to assuage secession, suggested interest in compromise with potential preservation. To avoid greater doubt over Lincoln’s move, the decision to only announce the Proclamation following a Union military victory was vital towards more solid support abroad. The Battle of Antietam in September presented this opportunity, avoiding the appearance of a desperate gamble following military disaster.

“Gentlemen, I trust that our abhorrence of slavery is not in the least abated or diminished. For my own part I consider it one of the most horrible crimes that yet disgraces humanity. But then, when we are treating of the relations which we bear to a community of men, I doubt whether it would be expedient or useful for humanity that we should introduce that new element of declaring that we will have no relations with a people who permit slavery to exist among them.”

– Earl Russell, British Foreign Minister

Speech at Blairgowrie, Scotland; September 26, 1863

British sympathy for the Union grew in the aftermath of the Emancipation Proclamation, though reservations over the matter of slavery remained within the government. Some saw the presence of slavery as a nonissue in discourse with the Confederacy, though they publicly retained stances against the practice. The South’s military performance in the latter half of the war served as more of an obstacle, as any additional support from Britain would have angered a victorious North. The growing prospect of public pressure, carrying political consequences, for any action deemed to support the South – and therefore, the preservation of slavery – further deterred such action.