“I have well understood that the duty of self preservation rests solely with the American people. But I have at the same time been aware that favour or disfavour of foreign nations might have a material influence in enlarging or prolonging the struggle in which the country is engaged.”

– Abraham Lincoln

Letter to the Working Men of Manchester, January 19, 1863

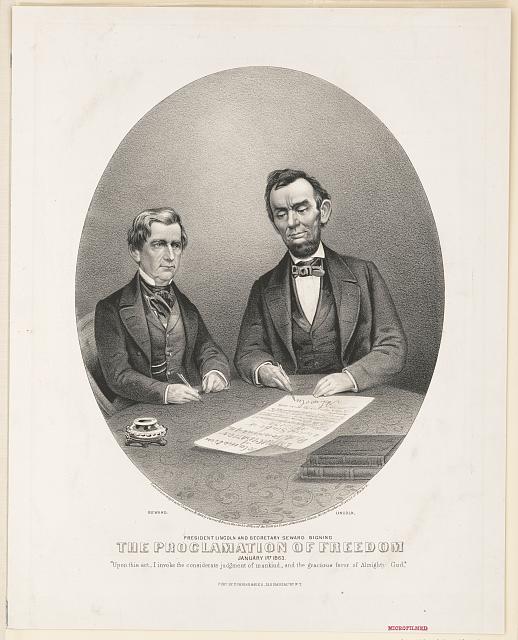

The 16th President of the United States presence in historical memory today often focuses on his role as commander-in-chief during the Civil War, or else for his part in the emancipation of the nation’s enslaved population. In diplomatic matters, Lincoln’s presence is less clearly displayed, Secretary of State William Seward, with his brash personality, more often the focus. Yet through U.S. foreign policy, particularly in diplomatic matters with Britain, Lincoln’s influence is felt.

(Image from the Library of Congress)

Most immediately, a key guiding principle for the Union’s diplomatic interests stems from Lincoln’s own musings on the matter. The real risk of a secondary war with a European power – be it with England over Southern support, or with France to address their invasion of Mexico – shadowed the work of the State Department at home and abroad. On the matter, particularly in highly contentious moments such as the Trent Affair of late 1861, the president took into account the risk to the nation, particularly to its immediate priorities. “One war at a time,” was Lincoln’s response to the idea of escalating military pressure as a diplomatic tool.

Lincoln’s image abroad varied throughout the conflict, differing from group to group. Entering into White House, his capability was often underestimated, having risen from Midwest obscurity to the House of Representatives, and later, a U.S. Senator. Even among the members of his incoming administration, early doubts existed over his performance as Chief Executive. Incidentally, William Seward was one individual holding such a view early on. Having opposed Lincoln during the Republican convention, Seward gradually formed a strong working relationship with the President. For his own part, Lincoln was inexperienced upon taking office, not versed in matters of wielding war and executive powers. In the first months of his presidency alone, Lincoln faced challenges few, if any, of his predecessors in the office had faced.

“But whatever policy we adopt, there must be an energetic prosecution of it. For this purpose, it must be somebody’s business to pursue and direct it incessantly. Either the President must do it himself and be all the while active in it, or devolve it on some member of his Cabinet.”

– William H. Seward, Secretary of State

Memo to the President, April 1, 1861

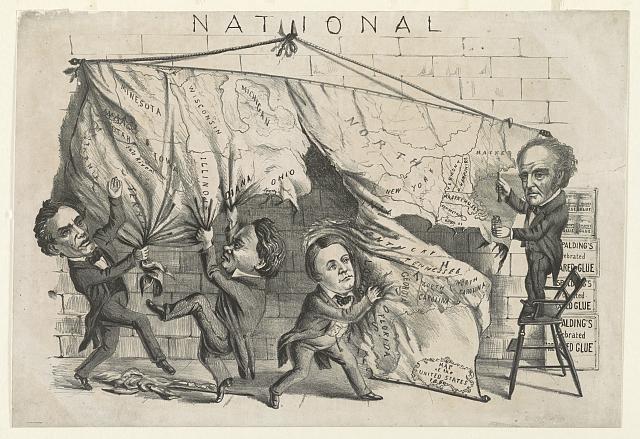

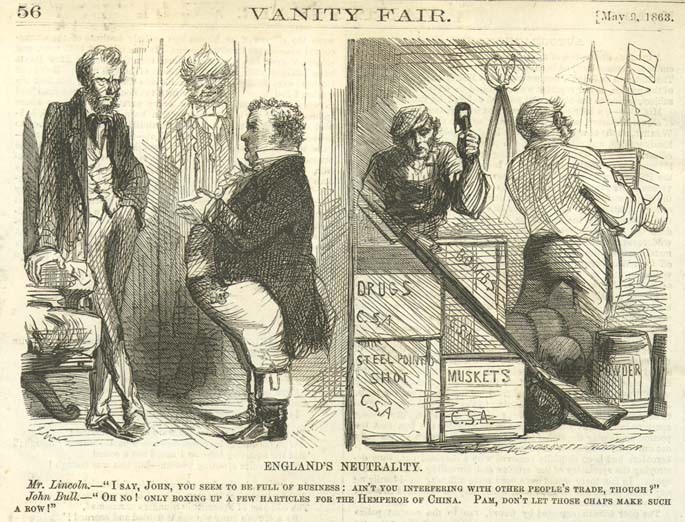

For foreign onlookers during the Civil War, Lincoln’s figure and character often drew the greatest attention in interpretations of the Union. Never travelling abroad during his administration, imagery and reporting described the president to the foreign public. Accounts of his unusual appearance and rustic wit garnered interest, feeding support and criticism abroad. Caricature of the President appeared throughout the British Press, satirizing the political and military troubles of the Union in the first years of the war.

“A person who met Mr. Lincoln in the street would not take him to be what – according to the usages of European society – is called a “gentleman;””

– William Howard Russell, London Times reporter

My Diary North and South, 1863

(Image from Special Collections and College Archives, Musselman Library, Gettysburg College)

Others criticized Lincoln for the nation’s approach to the matter of slavery. Publicly advocating a greater focus on reunification rather than any cause of emancipation at the war’s outset, Lincoln’s justifications for war spread confusion over the aims of the North. The president’s announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in late 1862 marked a shift, presenting a clear line of separation for the war – between a cause of freedom and liberty, and one of enduring slavery. Both Lincoln’s own approach and the influence of his cabinet shaped how this transition occurred. Seward in particular supported the necessity of grounding the President’s action upon a military victory, to strengthen the Proclamation’s impact with foreign onlookers, leading to Lincoln’s use of the Battle of Antietam.

(Image from the Library of Congress)

Following President Lincoln’s assassination in April, 1865, days after the end of the war, memory of his character abroad centered upon his role as a reformer. In the aftermath, honors and eulogies to Lincoln appeared around the world. His actions promoting democracy and emancipation drove up support among foreign working classes, particularly in the United Kingdom. Such an impact persisted past the President’s death, serving as an inspiration to post-Civil War social and political reform efforts in Britain. Despite never stepping on foreign soil, Abraham Lincoln’s influence upon American diplomatic policy and appeal across the international public supports the perception of a broader global impact.