For his wealth is without measure,

Far surpassing Northern treasure.

Great King Cotton.

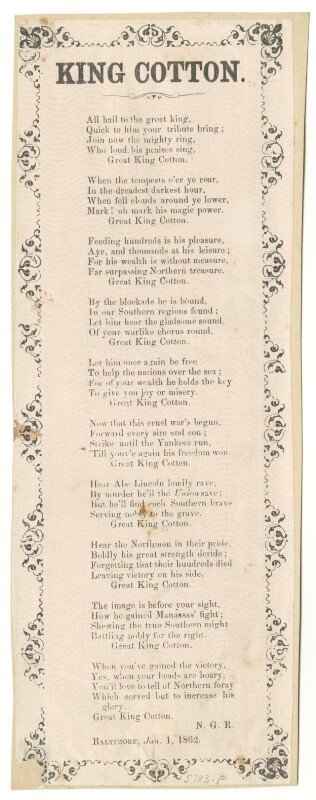

– King Cotton, lyrics by Nicholas G. Ridgely, June 1st, 1862

The economic craze over the production of the cotton crop dominated much pf the mid to late antebellum South. This preeminence of the region’s singular agricultural focus made it a key supplier of global markets – a keystone of the Southern economic system. The theme that developed – that ‘Cotton is King’ – influenced much of Southern society and culture. Art – imagery, literature and music – were created to espouse the glories of ‘King Cotton.’ Given form most often in mediums of print and imagery, particularly cartoons, the themes it carried could give it the form of a wealthy, majestic ruler on a throne in favorable depictions – or a miserly figure on shaky ground in unfavorable presentations. These latter depictions often highlighted the perceived arrogance of the South in uplifting cotton above all, and particularly targeted the ‘King’s’ increasing dependence on slave labor to maintain his throne.

A song sheet written by Nicholas Ridgely in 1862, celebrating the glories of Confederate soldiers, portraying the influence and wealth of cotton as leading the way towards a Southern victory.

As the above wartime lyrics suggest, positive portrayals of ‘King Cotton’ – in all of his forms – was synonymous with the perceived prestige and renown of the region in the public eye, particularly those of the wealthy and influential plantations. This mindset around cotton planting both derived from and drove its growth westward over the early 19th century. However, with this movement came the continued expansion of slavery into the west, supporting cotton’s dominance across the South.

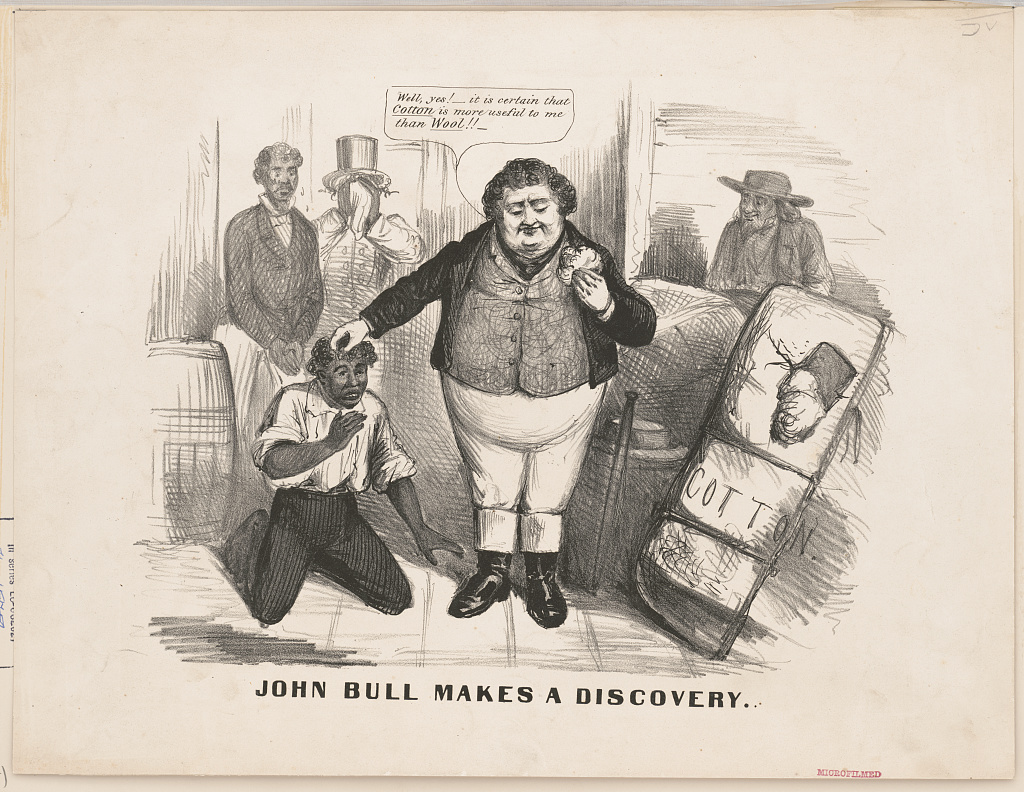

With the outbreak of secession followed by Civil War, the status of cotton became a cornerstone of Confederate outreach. Its economic influence in European markets – the reliance of textile industries in England and France upon Southern production of the raw material – made it central to early diplomatic planning. Arguments that brought up the Union’s blockade of the South, cutting off trade, and the South’s own idea to place an informal embargo on cotton prior to being cut off comprised cotton diplomacy. However, despite repeated attempts across multiple years and over successive Confederate Secretaries of State, such outreach failed to catalyze outside support.

The issue of continued dependence on the propagation of slavery to support cotton production served as a constant impediment to swaying foreign public opinion of the Southern cause. On the part of foreign governments, while less concerned about slavery, other economic and political interests undercut the influence of cotton diplomacy. Agricultural production in the North, in the breadbasket states of the early mid-west, provided a key supply of grains and other crops to European powers. Recognizing their importance, and having a stockpile of cotton left over from before the conflict, these nations were less inclined to intervene, lest they risk losing crucial trade connections.

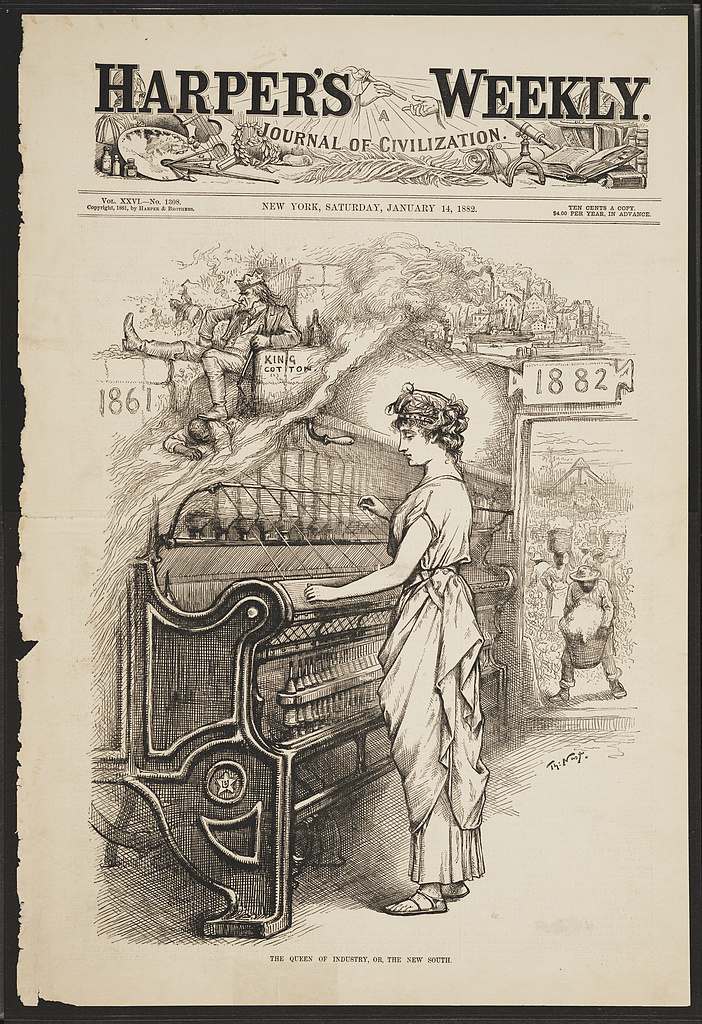

The damage to the South’s economy and production capability caused by the ravages of the war crippled it in the years that followed. The destruction of the slave labor system it had depended upon irrevocably transformed the course of the region’s development, though the growth of cotton did not entirely abate. The continued dependence on the crop in different corners of the South, even as the region rebuilt and incorporated additional industrial infrastructure, largely supported by black and white sharecroppers, suggests that King Cotton mentality had not disappeared. While the antebellum themes of glory and prestige had collapsed, its economic importance to the ‘New South’ remained.