“Nothing but “War, and rumors of War,” are heard here. All expect, and all accept it, and generally with less reluctance than I anticipated. It is unfortunately, assumed that we are unfriendly to England, and are seeking a quarrel.”

– Thurlow Weed, Union Agent in Britain

Thurlow Weed’s Letters from Europe, December 7, 1861

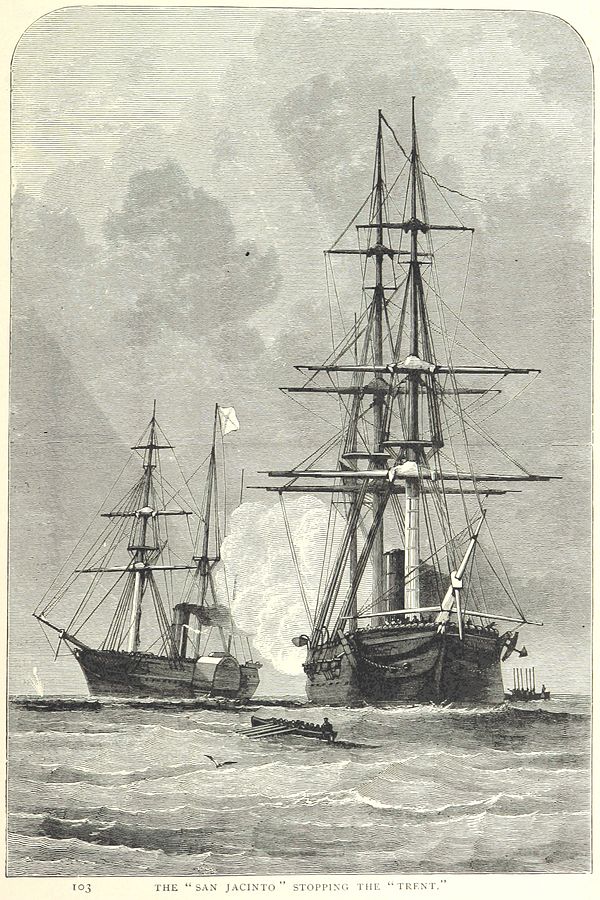

1887 Print from The Youth’s History of the United States, published by Cassel & Co.

The onset of Civil War in 1861 presented diplomatic challenges for the Union and Confederacy alike. From the North, the Lincoln Administration struggled to clearly justify bringing war against states seeking independence. Their efforts rested on the prevention of outside sympathy and assistance to the Confederacy, work that suffered further from poor military performances by the Union in the first year. While it’s blockade had not yet been challenged by the British or other European powers, the potential that such a threat could emerge was not ignored by President Lincoln or by Secretary of State William Seward.

In the South, the failure of early outreach efforts dashed hopes in the Davis administration that Europe would rally to support their cause. Furthermore, their troubles were compounding by shifting leadership over foreign policy. Three seperate individuals officially served as Confederate Secretary of State between 1861 and 1862 – Robert Toombs, Robert M.T Hunter, and Judah P. Benjamin. The first two only serving months on the job, often prioritzing the largely failed strategy of cotton diplomacy, only Benjamin stayed in the position, lasting through to the end of the war.

The end of 1861 presented a new challenge for the Union, and a vital opportunity for the South. From early November through to the New Year, the U.S. and Britain were embroiled in diplomatic turmoil. The Trent Affair, emerging from the arrest of Confederate diplomats James Mason and John Slidell by U.S. forces while aboard a British packet ship. From this came accusations of neutrality violations, nearly bringing about a military escalation to the situation. Representing the closest point to a conflict breaking out between the U.S. and Britain during the Civil War, the Affair reflects the importance of diplomacy to the course of the struggle.

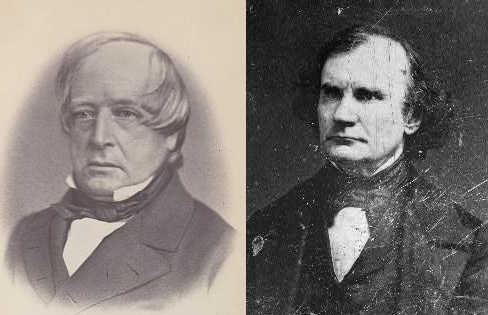

John Slidell and James Mason leave the South

Assigned their diplomatic posts in England and France respectively, the two Confederate envoys travel from Charleston Harbor. On-route to the Caribbean, their ship runs the Union blockade, not yet at its full strength, eventually reaching Cuba. Intending to take a neutral vessel to reach England and avoid Northern interference in their mission, news of their presence on the island soon spreads, reaching the ears of the Union.

(Images from the Library of Congress)

Departure from Havana

Amid Union interest in the capture of the Confederate diplomats, the planned date of the departure of Mason and Slidell from Cuba had become known to Union forces. Aboard the British mail carrier RMS Trent, precedent in maritime and neutrality law suggested them safe from any attempt at their arrest. However, Union forces, specifically the USS San Jacinto under Captain Charles Wilkes, moved to catch the Trent and remove its special passengers before the ship reached British waters.

Union Interception

Stopping the Trent before it left the Caribbean, by firing warning shots across the bow of the mail ship, crewmen of the San Jacinto board the British vessel. Treating its diplomatic passengers as transported contraband not protected under Britain’s neutrality, Mason, Slidell and their aides are taken from the Trent. Wilkes, believing that he operated in the interests of Union war efforts, places them under arrest. The packet ship and its passengers are allowed to continue on their way, eventually reaching England.

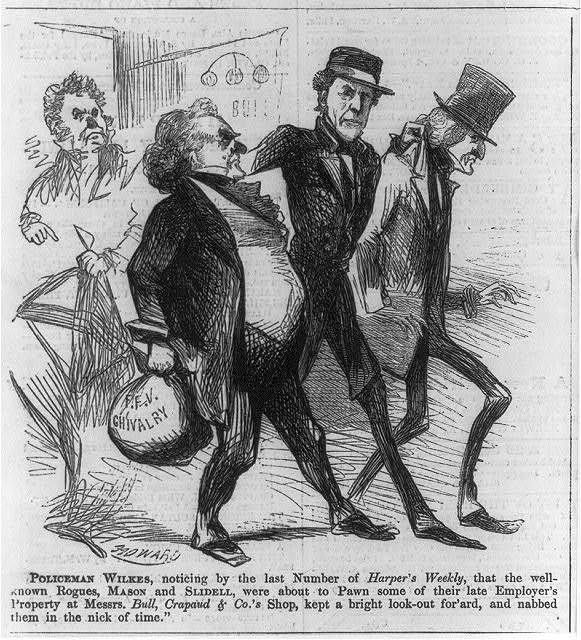

Reception of the San Jacinto

News of ‘Policeman’ Wilkes’s actions and the arrest of the Confederacy’s diplomats soon reached Washington D.C., the story spreading across the country. Immediate public reaction in the North, lauded the actions of the San Jacinto‘s captain, with criticism of the captives, the Confederacy and the British role. Even among the inner circles of the Lincoln administration, the capture was well-received. However, with revelations on the British response to the Affair, the U.S. position grew weaker, and Wilkes fell under new scrutiny.

(Image from the Library of Congress)

The British Reaction

Almost immediately following news of the Trent‘s stopping and the removal of her Confederate passengers, perceptions of the incident considered it in violation of British neutrality, an insult to the nation’s honor and, to some, an act of war. Confusion abounded over where responsibility lay behind the actions that created the Affair, drawing connections between Wilkes’s decisions and the interests of prominent Union figures, including William Seward. Further news of American sentiment following the event did not improve British feeling going into December, with threatening calls for escalatory action.

(Image from the Library Company of Philadelphia)

“It thus appears that certain individuals have been forcibly taken from on board a British vessel, the ship of a neutral Power, while such vessel was pursuing a lawful and innocent voyage, an act of violence which was an affront to the British flag and a violation of international law.”

– Earl Russell, British Foreign Minister

Dispatch to Lord Lyons, British Minister to the U.S., November 30, 1861

The British Response

Early drafts for the Empire’s response to Union’s perceived slight against them took an aggressive approach, aggressively responding as to a provocation for war. The demands for the release of the arrested diplomats, as well as a formal apology to Britain, remained consistent, though the tone of the formal communication shifted. Largely in part due to revisions by Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert (pictured), the new dispatches avoid excessively confrontational tact.

(Image from the Library of Congress)

Earl Russell’s Ultimatum

Accompanying the formal requests from the British government, the Foreign Minister, Earl Russell, communicates to the British minister to the U.S., Lord Lyons, a further request. To be delivered to Secretary Seward, Russell’s message lays out an ultimatum for a formal U.S. response to British inquiry and challenges, initially carrying with it a seven-day deadline to respond. Preceding the arrival of the message, Russell’s government was increasingly looking at preemptive measures, taking action to secure its North American territories in the event of further escalation.

Lincoln Acquiesces

Compromising on the parameters of Russell’s seven-day deadline with British Minister Lyons, Seward and the rest of Lincoln’s Cabinet debated the consequences of any decision on the diplomats’ release. Arguing for their release, Seward noted the risks posed by a refusal of British demands. Lincoln’s own interests in avoiding an unnecessary war with Britain over the issue override his misgivings over Mason and Slidell’s freedom., and Seward’s proposal went forward. The Secretary then crafted a response deeming Captain Wilkes’s actions to have been made of his own accord, disavowing any responsibility on the U.S.’s part.

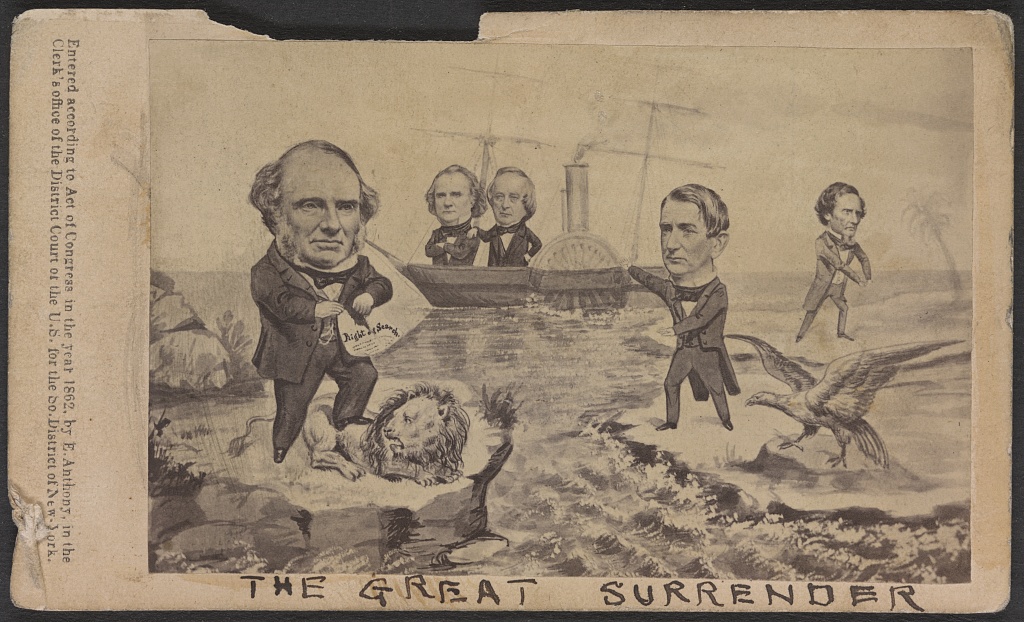

Mason and Slidell Freed

Sailing from Massachusetts aboard a British warship, the HMS Rinaldo, the freedom of the Confederate diplomats came amid mixed reaction from the American public over their release and the part that grievances raised by the British had played. . While diplomatic tensions began to cool, public distrust and frustration remained. Confederate hopes for the outbreak of a second warfront were dashed, overall gaining little from the Affair. These elements are reflected in the caricatures of the 1862 print above, titled ‘The Great Surrender,’ satirizing each side of the issue.

(Image from the Library of Congress)

The outcome of the Trent Affair resolved immediate diplomatic tension, though animosity between the North and the British remained, with additional flareups over perceived violations of British neutrality throughout the remainder of the war. Among the enduring effects of the incident was the strengthening of the military presence and security of the Canadian provinces, later contributing to their political reorganization as part of the Canadian Confederation’s creation in 1867.

Diplomatically, the Affair further made clear to the U.S. the necessity of good relations with interested European nations in the first years of the war. Efforts to avoid repetition of the 1861 escalation guided later diplomatic talks and Union complaints over Confederate activity in Britain. It directly contributed to Secretary Seward’s interests in dialogue with Lord Lyons over the course of early 1862, which resulted in the Lyons-Seward Treaty aimed combating the Atlantic slave trade. Built upon throughout the war, and coming to fruition in the years that followed, more amiable relations gradually developed. The course of the Affair, representing the closest point to a secondary Anglo-American conflict during the Civil War, exemplifies the importance of diplomacy to the War’s outcome. The decisions made regarding the case of the Trent in 1861 carried the potential to drastically alter the nature of the conflict going forward.

“The Trent affair has proved thus far somewhat in the nature of a sharp thunderstorm which has burst without doing any harm, and the consequence has been a decided improvement of the state of the atmosphere. Our English friends are pleased with themselves and pleased with us for having given them the opportunity to be so. The natural effect is to reduce the apparent dimensions of all other causes of offense”

– Charles Francis Adams, Sr., American Minister to Britain

Letter to his son, Charles Francis Adams, Jr., February 21, 1862