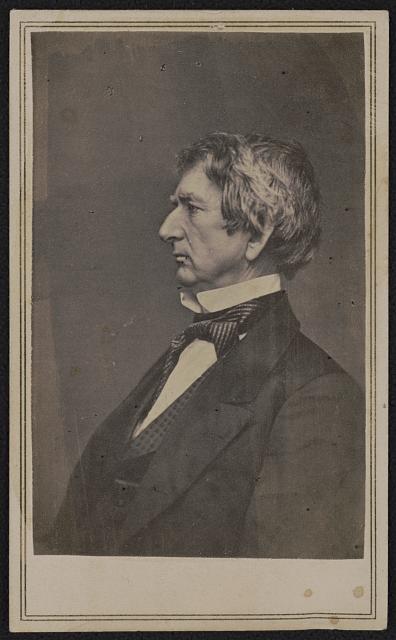

William Seward

Formerly a rival to Lincoln in the race for the Republican presidential primaries of 1860, Seward was given the position of Secretary of State following Lincoln’s election. Known for a combative personality, Seward’s office and behavior garnered him most attention in connection with the U.S. diplomatic presence.

An ardent Republican, he was particularly focused upon preventing foreign assistance of the South, raising questions of what constituted possible intervention by neutral powers such as Britain. His known interests in the U.S. acquisition of British Canada factored into rising British concern over the security of the North American territories. Seward found success in striking a balance between a forceful and a conciliatory approach, factors in the deterrence of Southern recognition and greater Confederate support.

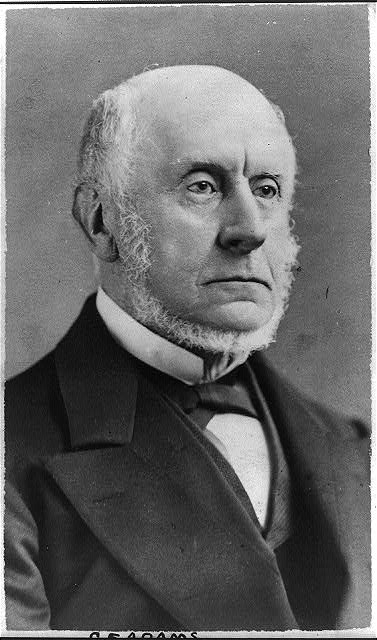

Charles Francis Adams, Sr.

Son of John Quincy Adams and grandson of John Adams, Charles Francis Adams was the primary representative for U.S. interests in the United Kingdom. His role as ambassador gave the Lincoln administration a window into the attitudes of British officials amid negotiations. Through his office, Adams worked to fulfill the aims set forth by Lincoln and Seward concerning Confederate outreach.

Acting alongside his British counterpart, Lord Lyons, Adams aided in the facilitation of dialogue and easing of tensions with British counterparts following controversies such as the Trent Affair. As knowledge of Confederate agents contracting British shipyards for new vessels spread, Adams put forth legal arguments for government seizure and the cessation of such activities, arguments that factored into post-war debate over British responsibility for Union naval damages.

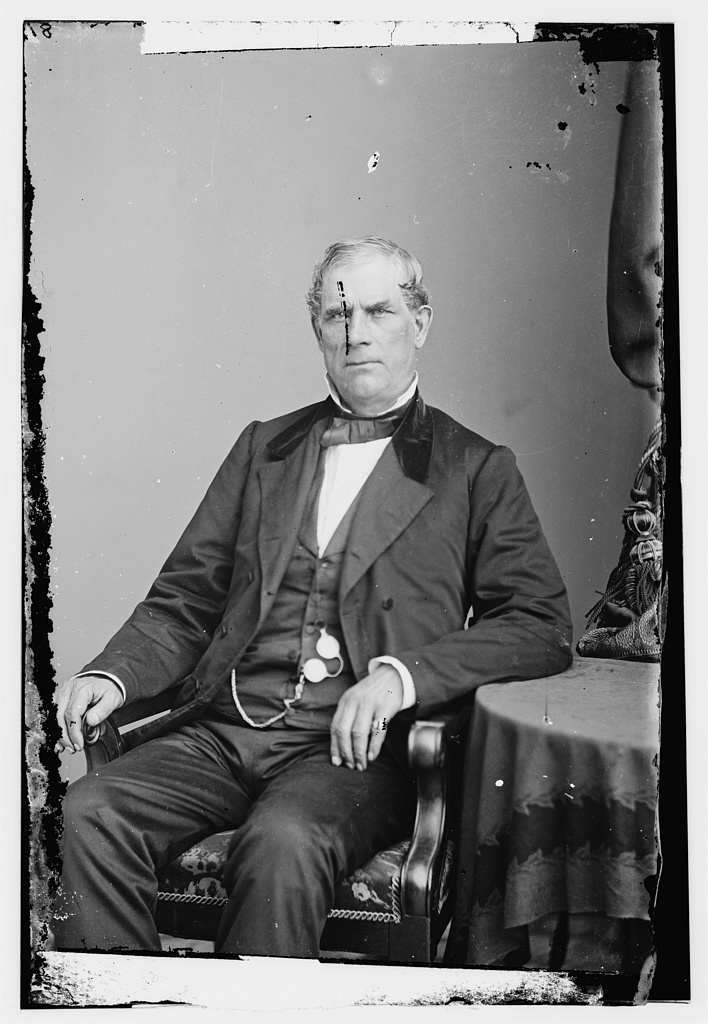

Thurlow Weed

A New York politician and printer, Thurlow Weed maintained a close correspondence with his friend William Seward through into the era of the Civil War. During the war, Weed travelled to Europe using his experience and formed connections to influence opinion in public and government circles.

His letters to Seward in this capacity provide insight into foreign attitudes and the arguments used by Americans working to sway them – both Union and Confederate. This is particularly true of correspondence concerning the Trent Affair of 1861. Written between late November and December, Weed describes the fluctuating feeling of the British public and Parliament concerning the controversy, including any interest or discussion in an escalation to the event.