The opening months of 1865 spelled the end for the Confederacy. Increasingly, Union raids and successes on the battlefield had lost them valuable ports, railroads and other resources necessary to continue the war. The final pursuit of General Robert E. Lee’s army by the forces of Ulysses S. Grant, culminating with Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House, ended any chance for a Confederate victory.

Lee’s defeat, and the fall of Richmond and flight of the Confederate government, marked the end of the Civil War. However, certain elements of the war persisted, and diplomatic issues that had arisen now garnered more focused attention from the United States. Both the government and the American people looked to the role of Britain throughout the conflict, leading both nations to act.

The Kenner Mission

In a last significant effort to gain foreign support for the Confederacy, diplomat Duncan Kenner arrives in England. His directives included the presentation of a plan promising the emancipation of Southern slaves in exchange for foreign support. The plan divided the Confederate government, its main provision unpopular with slaveholding politicians. However, support from President Davis and Robert E. Lee pushed the proposal forward. In the end, Kenner’s mission proved fruitless, as by this point Britain, France, and others deemed any such investment too risky, more likely to permanently damage relations with a inevitably victorious U.S.

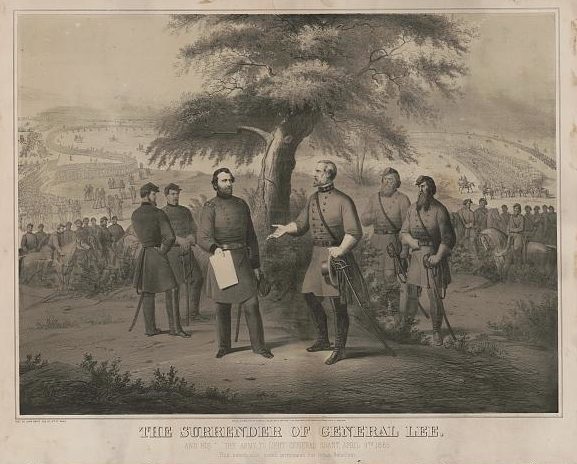

Lee and Grant at Appomattox

After a pursuit through Virginia, the heavily outnumbered Confederate Army of Northern Virginia under Robert E. Lee surrenders when finally cornered by Union forces. Confederate leadership had evacuated their capital at Richmond a week earlier, with many being captured or fleeing the country, and Lee’s defeat effectively ends the war for the South. Fractured elements of the Confederacy’s military forces remain, gradually surrendering over the remainder of the year. Soldiers and political figures alike find refuge as exiles in Europe, Canada, Mexico, and South America.

(Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Lincoln’s Assassination

Shortly after Lee’s surrender, President Lincoln is shot by John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theater in Washington D.C., dying the next day. The loss of Lincoln irremovably changes the approach taken to post-war issues, including policies of American Reconstruction and diplomacy. Honors to the late president come from around the world, with Lincoln’s role serving as an inspiration to contemporary and later reform efforts in the U.S. and Europe.

The Shenandoah Surrenders

The last military surrender in the Civil War, the crew of the Confederate commerce raider Shenandoah arrives in Liverpool and give themselves in to British custody. A former British merchant vessel, her acquisition and use by the Confederate Navy raised questions of British neutrality, much like the Alabama had. While the ship was treated as U.S. property and turned over to their possession, it is later sold in the United Kingdom. The Shenandoah‘s officers and crew escaped punishment, being released by British authorities and gradually dispersing around the world. Some would return to the U.S. years after the war.

(Image courtesy of the U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command)

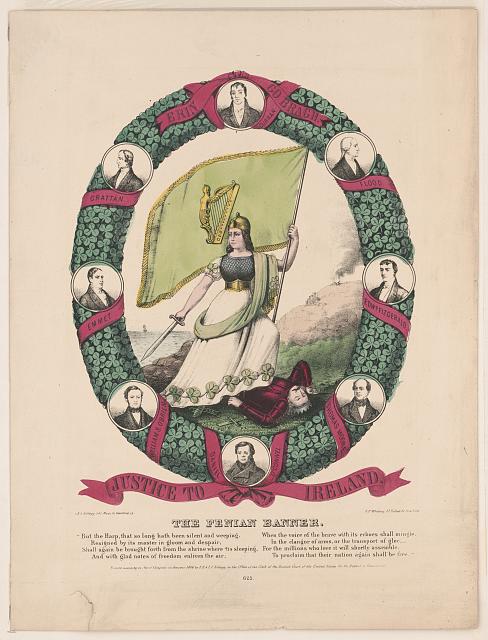

The Fenian Raids

In the first of two periods of raiding upon the provinces of British Canada by Irish Republicans staging attacks from the United States, Canadian and British forces successfully defend. A banner of the movement pictured above, the Fenians, upset over continued British rule over Ireland, intended their raids on Canada as a means to pressure the British to leave the island. The failure of the 1866 attacks leads to additional attempts from 1870-1871. Both periods leave Canadians drawing connection between the Fenians and American anger over perceived British and Canadian support for the Confederacy during the Civil War.

(Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

A Canadian Confederation

Responding to the military threat posed by the United States, the Fenian attacks, and territorial interests within the American public concerning the annexation of Canada, the British government takes action to reinforce the region’s security. To address these and longstanding issues in the governance of Canada, the provinces are reorganized to form a more cohesive system. Canada (formed by an earlier union of Upper and Lower Canada), New Brunswick and Nova Scotia consolidate under a singular dominion, a Confederation with power consolidated at a federal level. Retaining the provinces’ ties to the British Crown, the framework laid forth in 1867 supported later expansions of the Confederation, forming the early modern appearance of Canada.

Britain’s Reform Act

Also known as the Representation of the People Act, the 1867 Reform Act was the first in a series of political reforms passed in the decades after the American Civil War. Calls for an expansion of democracy, particularly concerned with participation in the political franchise, grew in the aftermath of the war. Reform groups were bolstered by the examples of Lincoln and action in the U.S. regarding the status and rights of black Americans during the early Reconstruction. Drawing upon earlier movements, such as the Chartists of the 1840s and 50s, the new waves pressured Parliament to act. In a limited, but still consequential move, the Act enfranchised portions of male working class populations of England and Wales.

Johnson-Clarendon Agreement

In an attempt to negotiate a settlement on the matter of the Alabama Claims, an agreement is reached between U.S. Minister to Britain Reverdy Johnson and British Foreign Secretary Lord Clarendon. The proposed treaty is opposed by many in Congress, which rejects it as part of the transition between the presidential administrations of Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant. The rejection of the deal revives political interest, particularly among more radical Republicans, in the issue of claims relating to the Alabama during Grant’s first term in office.

The Treaty of Washington

In a successful attempt a negotiation over the matter of the Alabama claims, the U.S. and U.K agree to the external arbitration of the issue by an international tribunal. Outlined by Secretary of State Hamilton Fish as part of a joint, twelve-person commission, the settlement also addressed other territorial and trade matters still lying between the two powers. This included separate arbitration, under Wilhelm I of Germany, regarding possession of the San Juan Islands off Oregon.

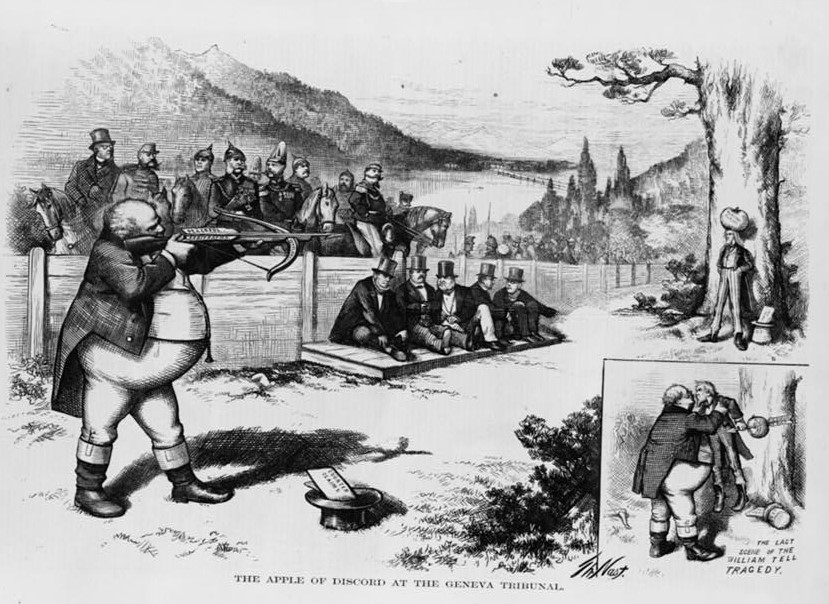

Alabama Claims Arbitrated

Concluding the matter of American claims and demands for recompense for the Alabama‘s actions, international arbitrators meeting in Geneva side with the American argument. Stemming from the Treaty of Washington, precedent for future such arbitration is established. Attendees included representatives from Italy, Switzerland, and Brazil – in addition to U.S. and British participation. The final decision required the British to pay 15.5 million dollars to the United States. The settlement, interpreted in the image above by Thomas Nast and Harper’s Weekly, sets the groundwork for stronger relations, removing obstacles and promoting a focus on the two nations’ shared interests going forward.

(Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)