The fear and furor for an Anglo-US conflict

At several points in the American Civil War, the Union threaded the needle of foreign controversy, narrowly avoiding a second military conflict both close to home and abroad. The potential for a concurrent war with Great Britain fluctuated throughout the first years of the main conflict, when neither North or South could achieve a definitive victory. The North did itself no favors in terms of foreign relations when the Lincoln administration embroiled itself in a diplomatic scandal. The last months of 1861 saw tensions between the United States and Great Britain rise almost to the point of military engagement, all over the case of Royal Mail Steamer named Trent.

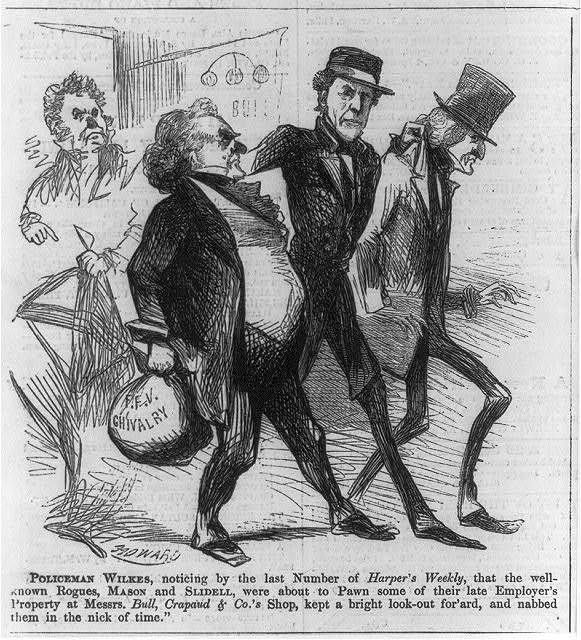

The RMS Trent had sailed out of Havana on return to Britain, carrying with it both standard deliveries and two particular passengers – Confederate Diplomats James Mason and John Slidell. Intercepted in the Caribbean by a Union Naval vessel under Captain Charles Wilkes, the Trent was stopped and the diplomats removed and arrested. The actions of the Union in this event caused a firestorm when the Trent finally reached its destination, shaking public opinion and the discourses of British government. Views that this action was a violation of the rights of neutral powers spread amid calls for a swift explanation from the U.S., and for the release of the diplomats. Many the North expressed both cheer at the capture of the diplomats as well as concern and frustration over British involvement in a ‘plot’ to bring these diplomats to Europe. It played into fears of outside intervention, and calls for the diplomats’ release were met with calls for a retaliation.

This post examines the topic of war during this period, examining multiple documents and correspondences connected to the diplomatic concerns and dialogues over the Trent controversy. Using the corpus tools provided by Voyant Tools, we can scan transcripts of these documents to determine the frequency with which the idea of war with Britain was discussed. These nine papers come from different backgrounds, from American politicians giving advice to Lincoln to American agents in London providing reports on public and government opinion.

Digitized images of the documents themselves, along with their transcripts, can be found on their respective item pages in the Omeka Collection. A page displaying the full Corpus page created through Voyant can be found here.

The documents include:

A letter from J.R. Doolittle to President Lincoln, December 19, 1861

A letter from Thomas Ewing to President Lincoln, December 28, 1861

A letter from Millard Fillmore to President Lincoln, December 16, 1861

A letter from the Prince de Joinville to President Lincoln, December 1, 1861

A missive from Earl Russell to Lord Lyons, November 30, 1861

Four letters from Thurlow Weed to William Seward, Dec. 4 (1), Dec. 4 (2), Dec. 11, Dec. 13

Looking at the frequency trends created by the corpus of these documents, the five words that appear most often are ‘government,’ ‘war,’ ‘Trent,’ ‘England,’ and ‘Great’ (used before Britain). ‘War’ is the second most frequent term across these letters, appearing twenty-three times in total, only surpassed by ‘government’ – a common term for discourse concerning representatives or discussion of policies and events between multiple nations. Surpassing the Lincoln letters of both former President Millard Fillmore and the French Prince de Joinville in discussing the threat of war with Britain are the concerns of Thurlow Weed in his correspondence to Secretary of State William Seward. In London as an unofficial American agent, Weed makes mention of war twelve times in his four letters back to Washington. Writing these over a period of roughly a week and a half between the 4th and the 13th, Weed’s fear is evident in the frequency of both his letters and his language in the early stages of the standoff.

The corpus formed by Voyant can provide more specific information about these documents and their writers’ perspectives using another format. looking at the document containing the highest frequency of ‘war,’ the longer of two letters Weed wrote to Secretary Seward on the 4th of December

The instances in which Weed mentions war in this first correspondence reflect the man’s rising concern over the situation as he understands it at that moment. “Prompt and efficient preparations for war.” “Already war steamers are being got ready.” Due to the context we have today, Weed’s observations can be connected to the height of the controversy, where a decision on the freedom of the Confederate diplomats had not been made by the Union and neither had an apology been delivered to Great Britain. The possible threat of the Union to British Canada prompted Parliament to order troop movements to reinforce the border while the Confederacy saw opportunity to sow tension despite their captive diplomats.

By the time of Weed’s letter to Seward from the 13th (data below), the situation has cooled slightly and the man has met with high-ranking British officials, including Foreign Minister Russell. Though war could still be considered a possibility, Weed appears reassured by his discussion with Russell and others that war is not desired as much as initial thinking had suggested.

President Lincoln received his own counsels on the matter, not just from men such as Seward – kept appraised of the situation in London by men such as Weed and the American minister Charles Francis Adams – but also by other prominent figures in American politics. Governors, representatives, and senators sent their thoughts on the Affair to the White House. One such letter-writer, the 12th president Millard Fillmore, offered thoughts on the war that reflected the consensus growing within Lincoln’s inner circle.

Fillmore’s use of ‘war,’ in the context of surrounding text, wars of the dangers of engaging enemies on multiple fronts – the “calamities of civil and foreign war at the same time.” The Union could not “take the hazards of a war at a most inconvenient time,” and expect to do well in either conflict it found itself in. What did the Union have to gain in prolonging this dispute over the captives that outweighed what it had to lose? Fillmore’s words convey the same general themes that structured Lincoln and Seward’s solution to easing the tensions caused by Trent.

Shown below, the Links format presented in the Corpus also reinforces these connections and themes. The words ‘time’ and ‘demand’ are both closely linked to ‘war’ in these writings, which itself is connected to ‘government.’ Groups in both the Union and Britain escalated calls for war, or at the least a demand for some response from their respective governments so as not to back down from the perceived slight they had recieved. The authors of these letters and others cautioned against these demands, expressing that it was not the time for a secondary conflict, that such a time could later, if the tensions caused by the situation persisted.

Ultimately, the philosophy of ‘One War at a Time’ proved the best possible course, in which the Confederate diplomats were returned to the custody of Great Britain, resolving the primary point of contention that had caused the dispute. Dispite fear and anger over the Affair, a possible second war had been averted for the present, though Anglo-Union relations for the rest of the American conflict remained shaky as Seward and his English counterparts worked to mend the divide.